With the annual Delivery Conference hosted by MetaPack having taken place this week, as the first New Year reunion of the industry there was plenty of analysis of peak and how this all went. Likewise, as the industry gathers together retailers and carriers took a look at what we can expect in 2018. Matthew Robertson, Co-CEO, NetDespatch shares his thoughts on the next year for retailers and asks if the Cost-to-Deliver is too high?

With the annual Delivery Conference hosted by MetaPack having taken place this week, as the first New Year reunion of the industry there was plenty of analysis of peak and how this all went. Likewise, as the industry gathers together retailers and carriers took a look at what we can expect in 2018. Matthew Robertson, Co-CEO, NetDespatch shares his thoughts on the next year for retailers and asks if the Cost-to-Deliver is too high?

Of course there are big issues like GDPR and Brexit on the horizon and more change anticipated as a result. Where ecommerce is concerned, there is no doubt that increasing consumer expectation is driving increasing need for rapid evolution within ecommerce. We can say hello to the ‘anything, anytime, anywhere’ customer who expects personalisation and convenience from their ecommerce delivery interactions. With 2018 expected to be another year of rapid change for exommerce, every business must look to evolve in order to turn change into new opportunities or risk getting left behind.

But when we talk about evolution, what does that mean in terms of delivery? And in our haste to get ahead are we neglecting to analyse what this might cost to the business?

There is no doubt that the burgeoning growth in omnichannel supply is great news for consumers and even enterprise buyers, but it also continues to add considerable complexity for supply chain organisations. In many cases, what I have witnessed first-hand is that many supplying companies have taken an “Implement first. Ask questions later” approach to multichannel and omnichannel strategies in their haste to avoid losing sales to ecommerce giants like Amazon. One of the key risks involved in such an approach is that certain sales will undoubtedly be unprofitable, and that’s an untenable situation for any company to remain in long term.

As businesses start to count the cost of omnichannel initiatives, it will be important to look closely at ways to streamline operations and improve profitability. In 2018 it will be more important than ever to perform detailed cost-to-serve analyses, not just to understand customer and product profitability, but also to determine the economics of the various order-to-cash pathways that make up the omnichannel supply chain. Of course this also means that cost-to-serve (CTS) analysis becomes more complex in an omnichannel environment, but that shouldn’t stop companies from homing in on CTS and other detailed cost evaluations.

Looking at the cost-to-serve not just in the supply chain but also in delivery is going to be critical in 2018, especially for some of the smaller organisations. Now with the peak selling season behind us, this is a good time of year to review arrangements with carriers and consider if your delivery cost could be reduced by making alternative arrangements, either with renegotiation of your rates or by switching carrier. Likewise, looking at the whole process and determining whether there are more parts of this that could be automated would be a good way to ensure that the cost-to-deliver is not becoming too onerous.

A recent study by Royal Mail revealed that the biggest costs that SME retailers expect in 2018 are purchasing (34%), logistics/delivery (32%) and advertising (27%). Reducing the cost of stock is probably more difficult as you need to have products to sell and most advertising rates are set rates, but there may be an opportunity to look at how you take costs out of the delivery process.

Switching carrier is often the simplest way to reduce your carriage rates. Your existing carrier already has your business and winning a new account is always a more attractive proposition than giving away margin to an existing customer. Plus, of course, your volumes since Christmas have probably dropped, giving your incumbent supplier even less incentive to lower your rate.

But another way to reduce your delivery costs is to consider the services that you use and offer your customers. Many retailers have in recent years lowered their standard service to an economy offering. Whilst there is often little difference in cost between a 24 and 48 hour service, if you’re shipping thousands of parcels per year this soon adds up. If you add on a day or so in handling time you may even be able to mitigate the slower courier delivery that comes with a 48 hour courier by speeding up despatch time in your warehouse.

Likewise, research that we have done in the past shows that consumers don’t always expect parcels to be delivered same day, or even the next day. Indeed, our research showed that in some cases if the goods they have ordered are a ‘nice to have’, rather than a ‘must have’, some respondents were happy to wait anywhere between 5 and 7 days for their parcel.

So, my advice is that now is the time to review and undertake a proper analysis of the cost-to-serve or the cost-to-deliver to customers and ask whether the service level you are delivering is truly necessary? Are there alternative delivery services that are less costly that you could be providing? Can you speed up your despatch time by automating your warehouse, pick and delivery processes? It is certainly worth exploring!

4 Responses

Having spent a fair amount of time working abroad, I don’t think our delivery services in this country offer great value for money, except for certain highly competitive parcel types.

Sending items overseas we find is nearly always much more expensive than the equivalent in the recipient country would be. We get consignments from the continent which often cost less than half what the UK despatch price would be.

One of the huge disappointments with RM privatisation. for example, is that the limited range of overseas services has not been improved in the slightest, whilst costs for overseas mail are rising at 10% a year. There is still no expedited airmail service since Swiftair was axed some years ago.

The problem is also that successive governments have made Britain a very expensive country in which to do business. All our infrastructure costs are elevated due to a mixture of privatisations and the drive to pay dividends to shareholders. When companies make efficiency savings, these rarely result in lower prices for customers. Additionally, when fuel was at a high price a while ago, carrier prices rose in response, but have not really come back down again, despite fuel returning to normal figures.

The only answer is to give the customer a range of choices and let them decide. You want it tomorrow? It will cost X amount. Happy to wait a week or so, then delivery is so much less.

the lemming like leap to offer instant delivery is the big problem

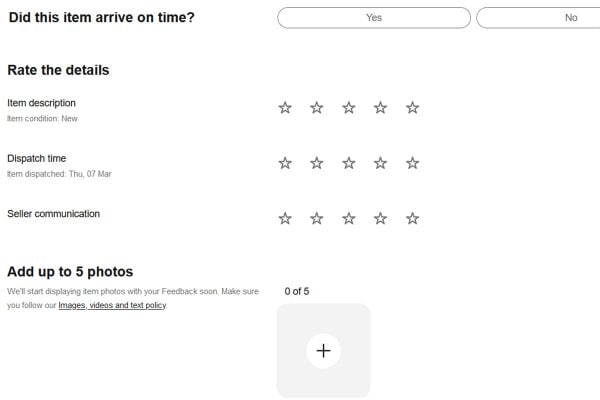

It’s been interesting to see that over the last few years it’s been the big retailers driving what delivery service the customer wants rather than the customer. Look around and the big boys are falling over themself to offer same day delivery etc. The problem is that the bigger companies have the setup and the money to do this, the rest of us dont. Customers then see this as the norm and anything else as slow. Add in the likes of Ebay who start hammering any seller that has a parcel that doesn’t arrive spot on time and there you have the issue. Dispatch is now our number one headache. We always point out that none of our services are guaranteed, yet public perception is increasingly becoming very unforgiving for even the slightest delay. Of course if the customer was actually in that would help…. but again some of the big guns have managed to encourage people to think that them not being in is the sellers fault too!

I really do fear that online retailing is in danger of creating a situation where what the customer was led to believe they could have, will become increasingly different to what they actually get.

There’s an old engineering joke about how you can have any two of fast, cheap or good, but not all three. The same is true when it comes to delivery. It’s not that delivery is too expensive, it’s that consumers don’t want to pay for it, so it has to be subsidised out of wafer-thin margins.

Ebay and Amazon have educated consumers that delivery should be “free”, and that should next day delivery should be standard. But free delivery means that from a seller’s point of view, it is a cost which has to be absorbed. There is no slack to truly subsidise it, and a lot of incentive to get delivery done as cheaply as possible. For the delivery companies under pressure on price, their margins are also tight, so their drivers are frequently subcontractors on very low wages.

Low wages = low spending power = pushing sellers on price, and the whole thing continues to spiral downward.

What is needed is for buyers to truly appreciate the convenience of a good delivery service, and be willing to pay a reasonable price for it. They need to recognise that each online delivery saves them the cost of fuel and parking if they were to buy from a High Street shop, plus the value of their time getting there and back and standing in a queue at the till.